As the industry reels in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, producers are already considering how to adapt their strategies. For those with significant assets in mature regions like the North Sea, any ban on drilling in the Gulf of Mexico is a problem. Ultimately exploration will have to continue but new technologies to improve recovery from existing wells could help buy time for the current storm to die down.

Even companies with their primary operations thousands of miles away from the affected region are feeling the effects. Statoil relies heavily on increasingly depleted fields on the Norwegian continental shelf, producing 70% of its oil in the area, and desperately needs to diversify its operations and had been eyeing up deepwater prospects in the Gulf.

Fortunately, there are options closer to home. At the end of June, the Norwegian government announced it would be making a further 94 blocks in the Norwegian and Barents seas available for exploration.

The industry had expected more but the country’s oil and energy minister announced that the six blocks closest to the coastline would not be offered in light of the Deepwater Horizon spill. Compared to other countries, Norway’s approach is upbeat and positive. Despite a Federal judge striking down the Obama administration’s moratorium on drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, interior secretary Ken Salazar appealed the decision and there remains the prospect of a ban.

The EU has also warned about the risks posed by subsea activities and Canada has made moves to block the drilling of new exploration and production wells.

See Also:

In the face of caution from regulating authorities and renewed hostility on the part of environmental groups, the industry needs to develop a clear strategy to bring it through the storm. Øystein Arvid Håland, Statoil’s head of subsurface technology, sees innovation playing a major role in improving recovery techniques and allowing the industry to demonstrate that it has made changes.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe first step, he suggests, will be greater standardisation of procedures in coordination with the International Standards Organisation and the American Petroleum Institute. “There will still be different authorities and regulations but I expect that the industry will work even harder at having some of the same standards worldwide,” Haland explains.

“It’s important to understand that it’s not just starting a load of paperwork but actually doing things that really count. Of course that’s why it is so important to understand what went wrong. “In every case there is something to learn – if you think you can’t learn anymore, you need to find something else to do. There will always be experiences that can be adapted and taken on board.”

The findings of the official investigation into the Deepwater Horizon incident should help producers demonstrate how they would avoid similar problems in the future and take steps to develop technology to bring wells under control in the event of an accident. “We have the relief well drilling technology but the problem is it takes a long time to get down to the reservoir,” Haland explains. “That is the one area where we’ll see some technology development and continuous planning.”

It is a message world leaders have signalled they will listen to. June’s Toronto G20 summit declaration noted, “Following the recent oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico we recognize the need to share best practices to protect the marine environment, prevent accidents related to offshore exploration and development, as well as transportation, and deal with their consequences.”

Technological progress will have to be backed by efforts from oil companies to clearly communicate the changes and improvements they are making. While Haland acknowledges that the chance of a major incident can never be completely eliminated, the appetite of governments and the public for drilling needs to be restored. “Our task is to give as many insights to the politicians as possible about safety and the levels of risk we’re talking about,” he says.

On the horizon

The comparatively positive attitude of Norway’s regulators means there is still scope for expansion at home but Statoil still faces the need to refocus its activities in the long term. The company has committed to maintaining production off Norway at its current rate of 1.5 million barrels per day but before Deepwater Horizon, it had announced plans for the coming decade that would begin to shift the balance of its operations away from the North Sea.

To achieve these twin goals Statoil has to combine an ambitious programme of exploration abroad with technological innovation at home and Håland has a significant role in the second element of the strategy. “Our plan states that it should be possible to maintain the level of production on the Norwegian shelf at the same level we have today,” he explains. “We aim to do it by working in existing reservoirs and bringing on new satellite areas.”

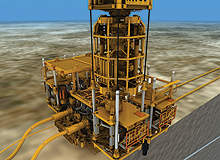

The newest tool at the company’s disposal is subsea throughtubing rotary drilling (TTRD). The technology enables the reuse of existing wells for new drilling projects, cutting back significantly on the capital expenditure required to access new cells, potentially making some minor satellites economically viable, and increasing recovery in existing fields.

The process involves drilling straight through the side of a well bore and does not require the ripping out of tubing. By eliminating the need for new Christmas trees and starting drilling deeper, costs and the time to production are kept down. TTRD has been in use on dry wellheads for a number of years but Statoil is the first to deploy it in subsea environments, which required compensating for the movement of the sea and delivering the drilling equipment to the well.

In late 2009, the company tested TTRD in its Asgard field off the north-western coast of Norway. Following the successful drilling of the new sidetrack well, Statoil announced it expected to unlock oil worth NOK 1.4bn (£145m) in that field alone and Håland sees the technology as an exciting step towards increasing the productive life of the North Sea.

“These huge fields are coming into decline,” he says, “but there are lots of opportunities to enhance recovery. There are some interesting business cases driving the need for this kind of technology and that’s a good position to be in.

“For years we have developed means to improve recovery from existing fields and utilise as much of the prior cap-ex and investment we have put into drilling down to the initial reservoirs as possible.” While the test was performed using a repurposed drilling rig, the company aims to bring a dedicated platform online by 2013 and is currently reviewing bids ahead of awarding the construction contract this autumn. “By implementing the new unit in a smart way, we hope to reduce the total cost by 40%,” Håland says. “We are also working hard to see how we can bundle other services together in a way that brings cost down to that level.”

The new method was designed in conjunction with subsea systems manufacturer FMC Technologies. Håland sees his company’s role as deriving competitive advantage though exploring new ways to deploy technology andwhile FMC had responsibility for providing the hardware, Statoil developed the overarching strategy and co-ordinated the activities of its partners.

Best of both worlds

Håland identifies integrating systems from a number of suppliers as one of the most challenging aspects of his role and building close relationships is essential to ensure long-term innovative thinking. “Entering into strategic alliances with our partners is a key aspect of our operating model,” he explains. “We see if we can agree on a technology development and if it is win-win then we will actually share some of the investment in the engineering phase.”

FMC received an award from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate, the country’s oil regulator, for its work on TTRD at Asgard. The award specifically cited the company’s courage for pressing ahead with technology without the guarantee of commercial success.

Håland acknowledges that the initial phases of an experimental design can be challenging. “When introducing new technology we always enter into a period during which we have to make investments and prove that it can work,” he says. “On the threshold of something new there will be uncertainties. I really believe the business opportunity is there, but of course investors have to be convinced that is the case.”

The company built a strong foundation by identifying which of its assets were ripe for further exploitation. Statoil produces 40% of its oil from almost 500 wells in mid-depth water, making the logic of pursuing TTRD clear. “There’s a very strong commitment to this from the top management,” Håland says. “The technology side is supported by the assets and we build the business case from there.”

A focus on continuous improvement not only of the core aspects of TTRD but also in terms of tools should help further boost performance. In addition, developing new techniques to control reservoirs and shut off segments will aid recovery in mature fields. While the technique has the greatest relevance to the Norwegian continental shelf, Håland sees potential for developing the technology for use in deeper waters such as those of the Gulf of Mexico.

Although Statoil currently has only limited operations in the region, he believes there could be licensing opportunities with other producers. While the company’s activities mark a new way of applying this technique, Haland is confident of its safety and notes that it could offer wider lessons about the implementation of new technology. “It is a concept that has been developed to be safe and maintain all necessary barriers between the surface and the reservoir,” he explains. “It’s a fit for purpose technology and that’s probably something we’re going to see more off in the North Sea, Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere – the development of new methods that will provide a better understanding of how to operate in these challenging environments.”

Although the industry has shown early signs of making a renewed commitment to safety measures, all of these advances are still to some extent dependent on oil prices. While Statoil has an internal guide price that impacts on investment decisions, Håland believes that the industry needs to learn a lesson about not flinching in the face of short term falls. “Today there are strong revenues from much of what we do and that lifts a lot of things,” he says. “We learned through oil price dips before that it was important to maintain production levels and cash flow. We need to understand that we should keep doing that but it is obviously more difficult to get capex when money is tight.

“If the oil price falls dramatically back down, things will become more challenging again – that’s the framework we always have to work under. At the moment I wouldn’t say there are any very black clouds in the sky, we just need to be prepared.”

While Håland might be optimistic as he looks to the horizon, the coming decade will be a period of transition for Statoil. It has been diversifying into North American shale gas and looking to the Arctic, which will be important if exploration in the Gulf of Mexico is put indefinitely on hold. With expansion away from the Norwegian continental shelf more difficult, technological developments aimed at older fields will have an increasingly important role to play.