In less than a decade, unmanned aerial systems (UAS) have evolved beyond their initial function as add-ons to traditional man-based inspection operations in the offshore oil and gas industry.

Drones are now used for everything from 3D modelling and surveying to aerial photography and security. Crucially, they have the potential to transform process and personnel safety by removing workers from high-risk environments associated with deepwater exploration and production (E&P).

Guidelines dictating the safe and timely use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) have so far struggled to keep pace with the technology’s rapid growth, something trade body Oil & Gas UK intends to address with its new UAS Operations Management Standards and Guidelines, published in January.

Developed by a work group comprising industry and aviation safety experts as well as UAS operators, the new document aims to achieve consistency with safety and operating standards already adopted on the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) for offshore oil and gas production and helicopter flight operations.

And, as Malcolm Connolly, founder and technical director of UAV company Cyberhawk, points out, it is by definition a work in progress that is subject to amendment as the sector matures.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData“Technology in this field is advancing so rapidly that in five years’ time there may be less need for UAV pilots, so these new guidelines are very much live and will need to be refreshed at a higher frequency than their manned aviation equivalent, which has been around for 100 years and has only experienced small incremental change,” he says.

“Cyberhawk was heavily involved in the new regulations and much of the content is based upon our standard operating procedures. What differs from the existing generic Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) guidelines is that UAV operators must now have a safety management system, an operations manual covering the specifics for oil and gas, and more stringent requirements related to pilot competency.

“The CAA guidelines contain a rudimentary flight test, but the new document advises a significantly higher level of task-based experience before a UAV pilot is put in an offshore oil and gas scenario.”

Fit for purpose: the new offshore UAV guidelines explained

Since Connolly founded Cyberhawk in 2008, the Scotland-headquartered outfit has performed more than 200 live flare and more than 5,000 structural inspections for more than 50 companies in 20 countries. He is uniquely placed to comment on the advancement of remote aerial technology, its application in the offshore environment, the operational risks and the importance of clearly defined regulations.

“A variety of organisations have produced UAS guidelines, including many national aviation authorities, which covered the gamut of commercial operations and were not industry specific,” he explains. “There are also a number of other industry bodies, such as the Helicopter Safety Advisory Committee, which identifies critical aviation issues in the Gulf of Mexico, who have produced guidelines specifically for the oil and gas industry. However, those documents were written from a desk-based perspective, not from an operational one, and there became a need for something more specific.

“As a member of Oil & Gas UK and the Air Safety Working Group, Cyberhawk was invited to become involved in the development of the new guidelines thanks to our vast operational experience. By involving UAS and aviation experts, duty holders – the oil and gas companies – and Oil & Gas UK as the facilitating body, the development of the guidelines has marked a step change for the industry. Other bodies which have previously developed guidelines have also taken note of this step change, and will potentially look to incorporate elements of the Oil & Gas UK rules.”

The guidelines provide information about best practice, procedures and the certification needed to be compliant with UAS regulations, with a special focus on operator training and system reliability.

“Cyberhawk’s minimum standards are higher than those specified in the guidelines; for example, we require our pilots to have a minimum of 500 hours’ flight experience before leading an offshore team, as opposed to the new guidelines which advise a minimum of 50 hours,” Connolly says. “The drones we use weigh around 2kg, so in terms of equipment reliability the normal manned aviation standards don’t really apply to UAVs. Instead, the technology must now have demonstrated 1,000 hours of operation and have a proven case history before it’s cleared for use offshore.”

Safety first: the risks and rewards of offshore drones

So what are the main applications for drones during offshore oil and gas operations, and the associated risks that remote technology poses compared with traditional manned aircraft?

“From an oil and gas point of view, we are predominately involved in the inspection of core assets at height − anywhere that is difficult to reach including drilling derricks, flare towers and exhaust stacks – and also underneath the platform in the form of under-deck drains, jackets, conductors and risers,” Connolly says. “Cyberhawk also carries out thermography and gas sensing tasks and drones can also be used for environmental monitoring, oil spill detection, even to deliver small packages to offshore platforms.

“In terms of risk compared with manned aviation, obviously drones do not carry anybody on-board and they are considerably smaller, meaning the consequences of failure are significantly lower. The biggest risk concerns conflict of operations, either with manned helicopters or other ongoing activities on the oil and gas platform. If a UAV came into contact with a helicopter that could potentially be a very bad scenario, so we don’t fly within a certain time period before and after an inbound flight. The same rule applies for crane and other simultaneous operations on a platform.”

The new Oil & Gas UK guidelines also encourage offshore operators employing drones to think about the whole operating and safety system offshore, and not just the air vehicle, as Connolly explains.

“Drones cannot work in isolation and therefore operators have to look at UAV technology and what other risks they are mitigating by using drones,” he states. “Working at height is the biggest single cause of industry fatalities. If using a drone takes people away from working at height, in a confined space or overside on a rig, then that must be weighed against the slight risk of, say, a drone crashing.

“There are also efforts to look at standardisation. All drones and drone operators are not equal and must have the right quality and safety management systems, and operational procedures in place.

“Often, an incident inspector or structural engineer procures UAV services, not an aviation expert, and so the new guidelines are also meant to give the people procuring UAS services a clearer idea of what they should be looking for when hiring drones in terms of an acceptable industry baseline.”

Remote possibilities: the evolution of the UAS industry

In addition to the possibility of pilotless UAVs, how does Connolly see the UAS market evolving in the short to mid-term, and what impact will that growth have on offshore oil and gas operations?

“At Cyberhawk, we are focused on processing the vast amounts of data drones can capture so that information becomes something of more value to our clients than simply a flat inspection report,” he says. “We’ve moved toward the back end software and asset management system to make it easier for offshore operators to assess the state of their assets. We are looking at the whole workflow now.

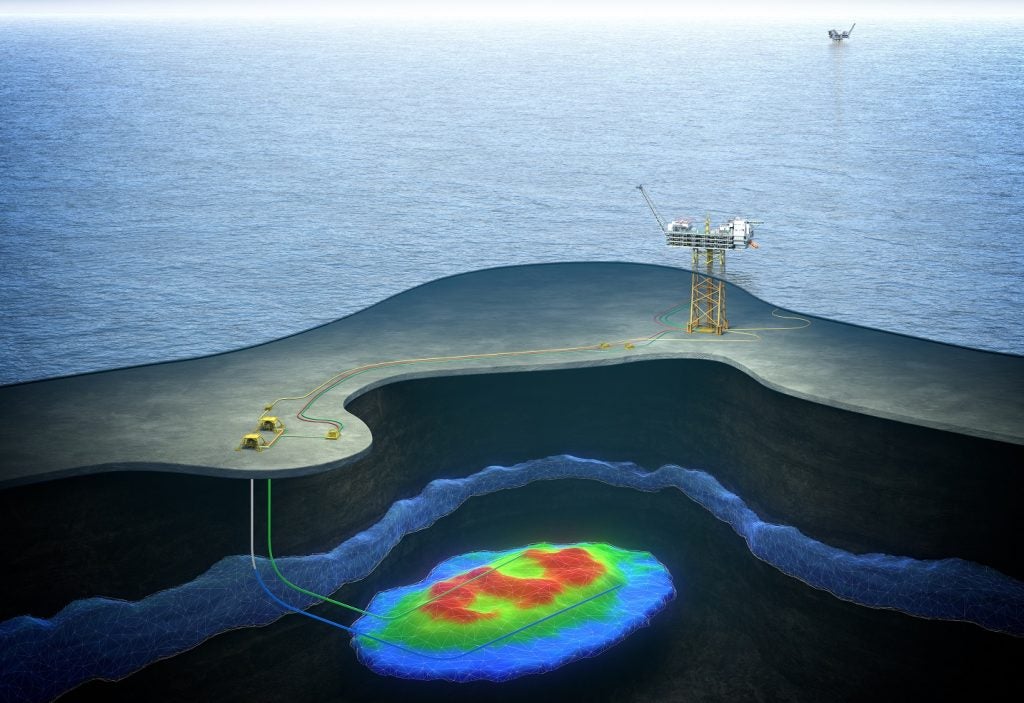

“Drones should been seen in the wider context of remote sensing that includes remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and smart monitoring. The subsea industry has been using ROVs for years and structures are now designed to be operated and maintained remotely because it’s just too deep for divers.

“Therefore, in the next five to ten years people will start to think about remote operations when they begin designing an offshore asset so they can be operated by remote flying and crawling vehicles. The introduction of the guidelines marks an important milestone in the sector and a recognition that adoption of UAS technology will continue to grow with a clearer set of guidelines to work to.”