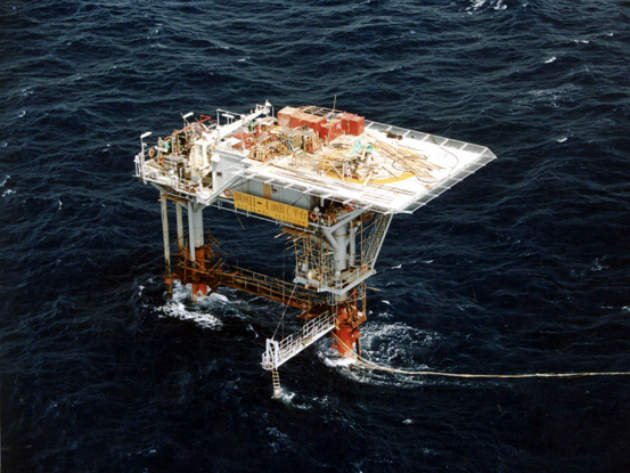

Strong domestic demand, declining output and historically low oil prices: Faced with this perfect storm, China’s government under President Xi Jinping decided that it had seen enough and in May announced reforms aimed at giving the market a more decisive role in China’s oil and gas industry.

After six years of stellar growth, production in the world’s second-largest economy began to decline at the end of 2015. Total yearly crude production fell by 6.9% in 2016 to 1.464bn barrels, China’s largest output drop since at least 1990. Bloomberg predicts a further drop of around 7% in 2017.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

“The increase in imports was further magnified by production declines amidst lower oil prices,” says Michal Meidan, lead analyst for Asian energy policies and geopolitics at consultancy Energy Aspects.

“In a low price environment, the Chinese Government seemed to ease some of its requirements to cap imports as it is also boosting stockpiles, but this year, with expectations of higher oil prices combined with a more tense geopolitical outlook, the government is keen to stabilise output.”

The reforms, a key plank of the nation’s 13th Five-Year Plan for 2016−2020, are intended to promote more diverse shareholder ownership of state-owned heavyweights such as China National Offshore Oil Corp (CNOOC), China Petrochemical Corp (Sinopec) and China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC).

“Market should play a decisive role in resource allocation and the government role should be better played in order to safeguard national energy security, boost productivity and meet people’s needs,” stated the reform guideline approved by China’s Central Committee (CPC) and the State Council.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe ultimate goal is greater efficiency as the world’s fifth-largest producer aims to increase domestic crude output to 200 million tonnes by 2020 and natural gas capacity to more than 360 billion cubic metres.

Monopoly money: how will reforms impact China’s big three?

National oil companies (NOCs) CNOOC, Sinopec and CNPC booked $600bn in revenue in 2016 and contributed nearly 9% of all the profits from China’s state-owned enterprises. Beijing has no interest in breaking up that monopoly; rather, the mixed ownership reforms are likely to be incremental.

“The mixed ownership reform is likely to have a limited impact on the oil market given that the majors are deeply entrenched in the upstream and midstream,” says Meidan. “However, in the gas markets, as pipeline and storage infrastructure are more limited, the entrance of new actors will help efficiencies in the medium term, provided they can survive an uncertain pricing environment.

“The mixed ownership reform is already starting to play out in trading as more non-state firms are allowed to import oil and natural gas, although they still face numerous hurdles such as a limited retail market for oil and restricted access to LNG-receiving terminals for gas.”

Reuters reports that Beijing’s strategy will be one of moderate, pilot-based changes such as granting licences to private refiners, establishing a private-led mega-refinery and overhauling management of state-run companies. Meidan concurs, but also points to pricing as a key element of future reforms.

“The oil and gas markets in China are at different stages,” she states.” The oil pricing mechanism changes more frequently than gas prices do and is therefore more reflective of global prices, though price movements are still determined by the government. The next step would be to reduce the role of the state in price setting, but this is unlikely to happen in 2017 and will only be achieved gradually.

“In the gas market, the next steps will be reducing pipeline tariffs and removing cross subsidies among end users − residential users, for example, pay around 30% less than industrial consumers. That said, lower gas prices will disincentivise domestic output while higher prices will crimp demand suggesting that natural gas demand in China will depend heavily on government policies.”

Private matter: the rise of China’s independent refiners

During China’s ‘golden decade’ between 2003-2013 − when global crude prices tripled − more than 1,000 private companies became genuine players in the nation’s previously monopolised oil sector, offering superior exploration, drilling and transportation services to inefficient state-run operators.

That private sector boom ended abruptly in 2014, killed off by a combination of plummeting global crude prices and the Chinese Government’s industry-wide anti-corruption campaign. Now, however, Meidan believes the return of independent companies is imminent, particularly refiners, known as “teapots”.

“The most salient feature of the Chinese oil market in the past 12−18 months has been the rise of the independent refiners and their appetite for imported crude at a time when demand growth is softening,” she says. “With higher refinery runs from independent refiners as well as new refining capacity additions, the main story in China is the adjustment in the downstream as a growing number of refiners compete for market share and grapple with changing product demand.

“The country’s economic transition from export-oriented growth to consumer-led development entails a shift from middle distillates to light ends, and the need to tackle worsening air quality also means more stringent fuel quality standards.”

Meidan also points out that China’s domestic gas output is rebounding as firms respond to pressure to boost production to satisfy escalating demand and hit the government’s environmental targets.

“Higher CAPEX investments in domestic upstream are benefitting gas more than oil, especially since demand is improving once more as the government is pushing to phase out coal use in boilers by the end of this year,” she says. “The key issue remains pricing as domestic prices are set by the state and respond very slowly to international pricing movements.”

Production targets: mergers, asset management and oil output

China’s big three oil companies have already responded to the reforms, led by Sinopec Group, which recently agreed to a pair of private companies, Chentong Holdings Group and China Reform Holdings, taking a 70% stake in SIPC, Sinopec’s overseas exploration and production company.

“It is unclear to what extent this will impact the majors,” says Meidan. “The main one to watch will be a pipeline company that will gradually strip the majors’ midstream assets and fold them into one company. The rumoured Sinochem-ChemChina merger will be another one to watch as the company may need to be broken up.”

So, is China’s stated goal of rise in domestic crude oil output to 200 million tonnes by 2020 realistic given the recent decline in production, and are the reforms unveiled in May sweeping enough to succeed?

“It will be challenging to reach the 200 million tonnes goal by 2020 given the CAPEX reductions over the past few years and the rising decline rates in China’s more mature fields,” says Meidan.

“That said, companies are starting to invest more in upstream development and with more output from offshore fields and potentially assets in Xinjiang province, production could manage to reach the 200 million tonnes in 2020. This year, however, the NOCs are unlikely to reach this goal.”