It has been said that the trouble with weather forecasting is that it is right too often to ignore, but wrong too often to be relied upon – and for the offshore industry, where the weather has such a huge bearing on so many activities, that has always been something of a problem.

Now, however, improved mathematical modelling and analysis is beginning to overcome these shortcomings and has the potential to bring much greater reliability and precision to forecasting within 10 years.

One of the institutions at the forefront of these moves is the Reading-based European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) – an independent inter-governmental organisation supported by 34 states, and backed by an annual budget of nearly £55 million. With some of the largest supercomputers in Europe, capable of more than 200 trillion floating point operations a second, and the world’s biggest meteorological data archive currently amounting to around 46 petabytes – and growing by the day – ECMWF is helping push back the boundaries of forecasting accuracy.

At the heart of it all lies numerical weather prediction (NWP) – a mathematical estimate of the future state of the atmosphere, based on a best assessment of its observed current conditions – but the chaotic nature of weather means that small errors fed into the model at the outset can mean big discrepancies in the forecast. Inevitably, the further ahead any prediction looks, the greater the uncertainty.

See Also:

Model comparisons

To mitigate against this, an approach called ensemble forecasting is used, which runs multiple versions of the computer model, each one with slightly altered initial conditions. Then, by seeing how similar or different the weather predictions in the many outputs – the ‘ensemble members’ – produced are, meteorologists can get a good idea of how likely any particular weather event is to occur, and weight their forecasts accordingly.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe ECMWF’s state-of-the-art ensemble prediction system (EPS) consists of 51 members, with one designated ‘control’ forecast, and the 50 others produced by small changes to the original initial state coupled with random mini-variations introduced to represent uncertainties in the modelling process. ECMWF’s Peter Bauer says that both individual member and ensemble predictions are continually evaluated and improved to produce physically consistent results that provide the most reliable global forecasts available today, with continuous evaluation being performed according to internationally agreed standards.

Liquid Robotics Oil & Gas celebrated its second birthday on the 1 July, vice president Sudhir Pai speaks about the journey thus far.

"Forecast reliability is rather accurate into the medium range, even for extreme weather such as storms, droughts and cold or warm spells," Bauer says. "A hundred percent reliability is not reachable but, statistically speaking, short-range forecasts of major weather patterns are close. The challenge is extending this skill further for extreme events and to small scales [to local weather] and beyond the medium range."

Site specific forecasts

With everything from scheduling the construction and movement of assets to the daily routines of drilling and production being highly weather dependent for the sector, knowing where something is going to happen can often be as important as knowing what.

The centre’s Tim Hewson says that the ability to generate accurate site specific forecasts has genuinely improved greatly over time, as weather models have been developed and refined, and there are very good reasons to expect things to continue to get better in future. Never-the-less, he warns that some things – such as pinpointing exactly when a shower and associated gusty winds will pass overhead – will remain virtually impossible in the medium range.

"Our strategy for countering this problem is to give probabilistic forecasts, that indicate in percentage terms the likelihood that showers and gusty winds will pass overhead during a given time window – which might be three or six hours long," he says.

The accuracy of these kinds of forecasts is also expected to improve in future.

Mixed blessing offshore

While there are obvious benefits for the sector to be had from reliable forecasting – not least in terms of cost reductions, optimised resource allocations and better risk mitigation and safety levels – it seems the offshore location itself is a mixed blessing when it comes to predicting the weather.

"In one sense forecasting for sites over the ocean, a long way from land, is more straightforward than forecasting for sites over or near to land because you don’t have the difficult complicating factors of hills and mountains, which can have a large influence on the weather, and on local winds in particular. In another sense forecasting for oceanic sites is more difficult due to the relative paucity of surface observations there, compared to over land, which are very useful for keeping abreast of complex developments in real time" Hewson says.

However, he states that although this aspect is only really relevant for short term forecasts – up to a day or so ahead – and so is not a focal point of ECMWF activity, the tendency for stronger and more variable winds to occur over the sea is an important factor that needs to be taken into account.

Wave prediction

ECMWF runs a prediction system which crunches the numbers around the energy contained in wave movements, including the boosting effect of those winds, to produce a two-dimensional ‘wave spectrum.’

As Peter Janssen explains, "from the wave spectrum all relevant sea state parameters such as wave height, wave direction, period and steepness of the wave may be obtained."

He says that there are two versions of the wave prediction system running – a global 28km grid and an 11km grid for European waters – allowing ECMWF to produce twice daily sea state forecasts, which are then disseminated to a large number of users, specialist commercial bureaux and offshore operators amongst them.

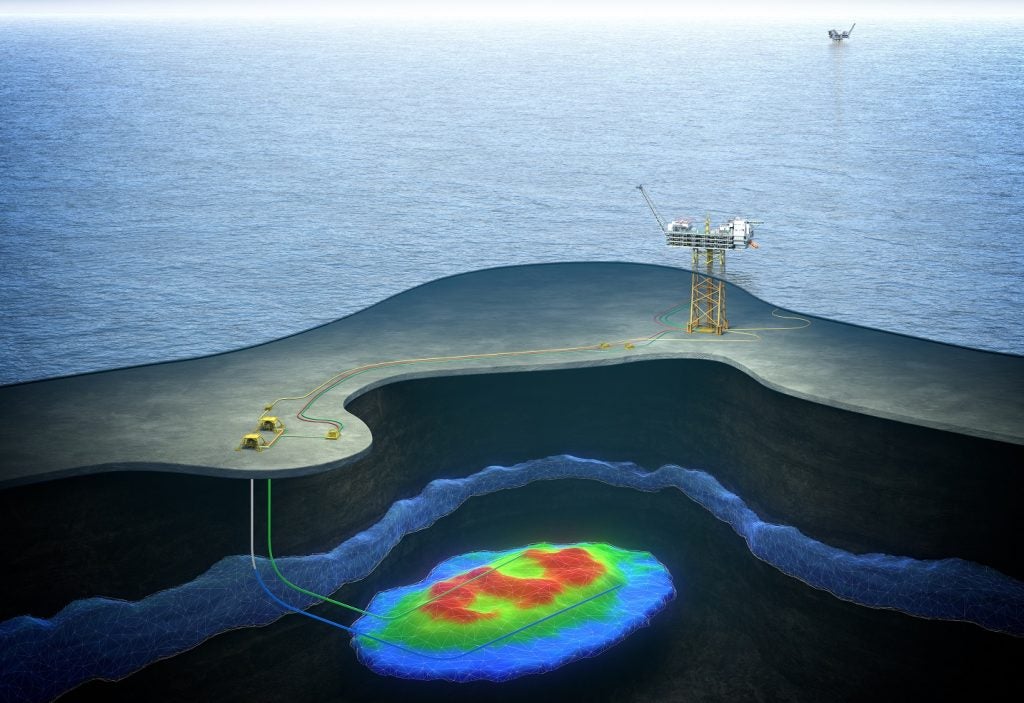

The iconic Forties Field in the UK North Sea is still pumping out oil 40 years after it was first brought on-stream.

Increasing model resolution

The field of forecasting is, like the weather itself, always developing, and the quest for high-resolution, reliable ensemble forecasts makes model development and error characterisation, better data usage and more efficient computing the main target areas of current NWP research. According to Bauer, no one single component is expected to yield a major breakthrough here, but the combination of these factors should ultimately produce the best prediction capability for the least computing cost.

"With increasing model resolution, the detail of the representation of physical processes in models needs to be improved as well as the accurate determination of initial conditions at that scale. This also requires new observation types being used."

He says that targeting the forecast range beyond one week, means that other components become important such as teleconnections – the long-distance linkage between weather patterns in widely separated parts of the planet – ocean and sea-ice processes, the upper atmosphere and the land surface. It all comes down to better spatial resolution and a more detailed process description, coupled with more complex models to take into account other ‘spheres’ – the hydrosphere, cryosphere and biosphere.

"All of this requires more computing power and new methods to run complex models on the available high-performance computers, with acceptable cost," Bauer says.

Improving numerical weather modelling is, of course, an iterative process, and one that takes time to refine, but in the long run, it holds the promise of forecasts of significantly enhanced precision and reliability – and for the offshore industry, that can only be good news.

.gif)