Scarlett Evans (SE): What does your team hope to achieve from the funding received?

Vahid Vaziri (VV): We are working on a wide range of projects, from novel drilling techniques to AI. One of the companies we are working with through OGIC is looking at analysing data taken from downhole calipers to understand the condition of the well being examined. The main thing we want to achieve across all of our projects is to help modernise the oil and gas industry. Although it is a relatively modern industry already, there are still some parts that are still conservative, because whatever they are doing has worked for years, so why should they change it?

Pressure from cost-cutting and environmental concerns are beginning to make people want things to be more efficient and have a lower carbon footprint. Over the last few years there has just been more motivation to use new technologies and modern science to streamline operations.

Any facility you see in oil and gas is already really impressive, but when you go into the details of techniques and machines, there are some parts that you can improve.

SE: What are some of the technologies your team are working on?

VV: Resonance Enhanced Drilling (RED) is the core of our novel and patented technology invented by CADR funding director, Professor Marian Wiercigroch, with the general idea being to change the basic mechanics behind drilling.

The traditional means of drilling uses pressure and rotation to cause a shearing, or gouging action that uses a low frequency and high amplitude that is actually quite dangerous and invasive. While it does work in some applications, it’s not widely popular as it compromises borehole stability. By contrast, RED uses a high frequency and low amplitude vibration to create a microcrack around the drill bit, making it far easier to shear, as well as less energy-intensive.

The main question we’re facing is how to produce this effect downhole, and how it will affect the rest of the drill string. We currently have two prototypes, which use different technology to produce the vibration, which we are testing in the lab.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataSE: How will recognising the formation being drilled improve operations?

VV: Ideally, in the future we want a tool that can read the data from what’s going on around it – the response of the vibration, and change its own frequency as it goes down. By using this technology that recognises the stiffness of the formation, you can get a much higher improvement factor and make operations much more efficient. All the engineering aspects of this already exists, the knowledge exists. Until now, it’s just been a question of licensing and finance, as well as the motivation to use it.

The first step is we are going to build and test a minimum viable product (MVP) for some field trials. As soon as we have done the trial, then we can move onto the next step. We have all the pieces of the puzzle, we just need to put them together.

SE: What else is your team looking at?

VV: We have also been looking quite extensively at drill-string dynamics. Drill string is prone to many sorts of self-induced vibrations because of bit-rock interactions, borehole drill-pipe interaction etc. We develop our own drill string lab to study its dynamics, bit-rock interactions, the performance of downhole tools and in general to predict what problems can come up while drilling, and how to mitigate them.

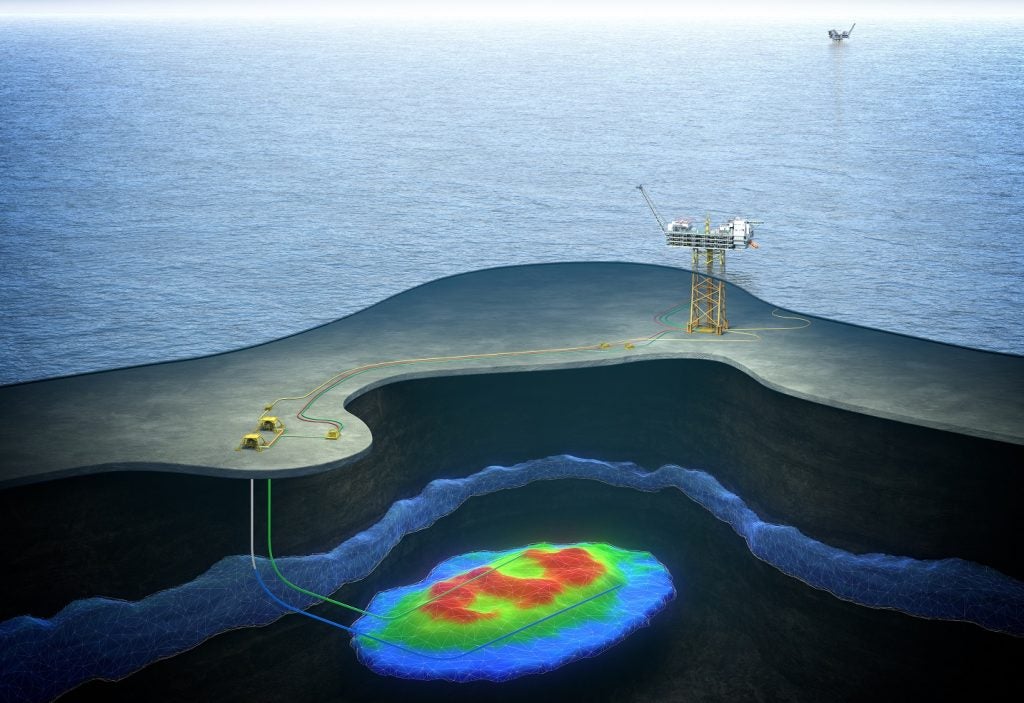

One of the worst-case scenarios in drilling is the ‘stick slip vibration’ – when the drill bit gets stuck, and then goes fast up to 10 times of its nominal speed. In this scenario, the drill bit can easily get damaged, and then you need to take a few km of the drill-pipe out and replace the drill bit. That’s cost – every moment in the rig is cost, especially in the offshore industry. So if you can reduce that, if you can avoid all these changes and time lost, that is not just money saved, it also helps to reduce environmental damage.

SE: When you look at the oil and gas industry, do you see it as an industry that has a lot of potential to continue growing with the use of new technology?

VV: I’m not in a position to talk about the entire industry’s future of course, but one this is clear to me: there are a lot of things, some of them very basic, that could use new technologies to improve.

Drilling is an obvious example of this. At the moment the most common way of drilling is just to exert force and torque to the drill-bit. But there are better ways – you need to think of how you can drill more efficiently, with a smaller carbon footprint. When you drill offshore, the energy you use has a very direct impact on the area around it. So you want to be able to drill in a much more delicate way, with a far smaller impact on the surrounding environment.

Improving the techniques used in oil and gas would also have a beneficial effect on the wider energy industry – such as geothermal. This method of energy production also requires drilling, and if you can drill to six or seven km, you would have much better access to the earth’s energy. Additionally, existing oil and gas technology can be used to inform the installation of wind turbines, we can install them on the offshore platforms we already have.

I don’t see improving technology in oil and gas as having a temporary benefit, it’s going to continue to be used in a variety of fields. Instead of starting things from scratch, we can apply these methods across the board.