Even before they are put to use, the production and distribution of fossil fuels is a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions: drilling, transporting and processing oil and gas emitted more than five billion tonnes of CO₂-equivalent in 2022, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Cutting emissions of methane, a potent GHG often released from oil and gas equipment, is a crucial tool to slow the rate of near-term global warming and will be a focus for action when the global community gathers for COP28 later this year in Dubai.

Globally traded companies like Chevron and Exxon are the most visible source of oil and gas pollution and face growing pressure to clean up their act. However, a far less visible group of energy companies is responsible for more than half of the industry’s emissions and tend to lag their private sector peers on key climate metrics like methane reduction: national oil companies (NOCs).

Ranging from giants like Saudi Aramco and Gazprom to small domestic producers, NOCs lack the brand name status of their multinational counterparts and are often seen as immune to public or investor engagement. Their priorities are closely tied to the politics and economics of their home government, and each has a unique profile of technical capacity and access to finance.

One commonality among NOCs is that the vast majority are not effectively managing their methane emissions. As NOCs play catch-up in the race to curb emissions, the finance sector has an important role to play in ensuring that NOCs get on pace with their peers in addressing methane.

IOCs taking some action on methane… NOCs not as much

After more than a decade of science-backed public, regulator and investor pressure, all seven global supermajors and many public and private energy companies acknowledge the importance of methane management. The global average methane intensity of oil and gas production fell by 5% between 2019 and 2022, and associated gas flaring, a practice closely associated with methane emissions, also declined somewhat. A key indicator of ambition on methane management is whether a company has joined the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership 2.0 (OGMP), which lays out a pathway to using direct methane measurement to target emission reductions: 100 operators representing almost 40% of global production have joined.

See Also:

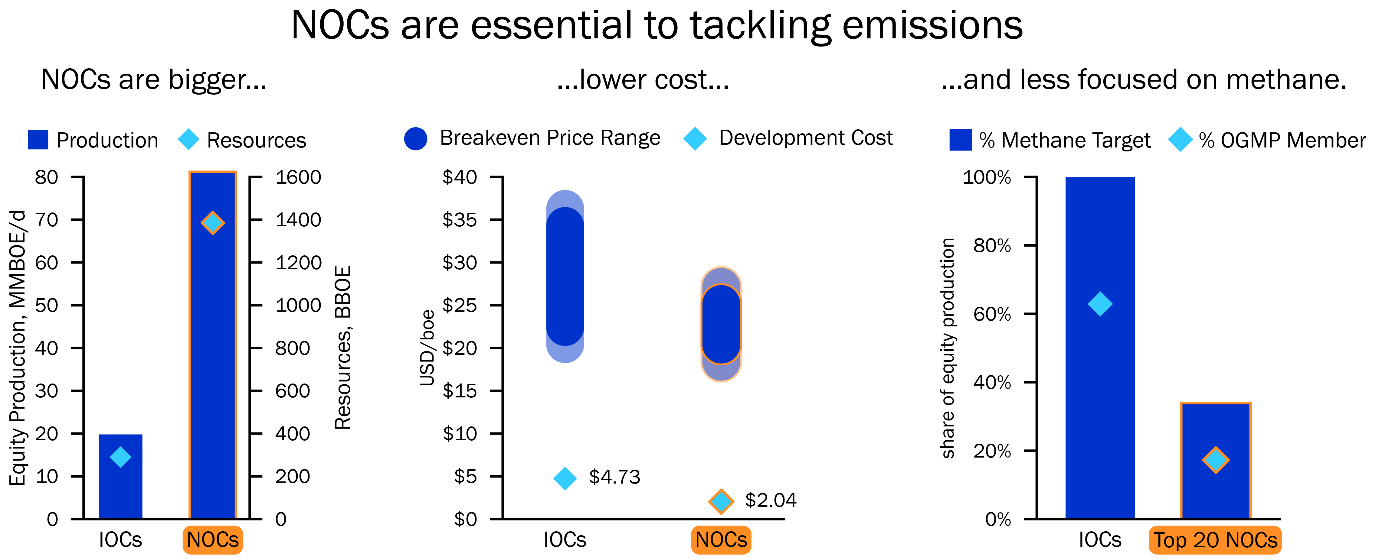

This is notable progress, but most of this action has been led by the international oil companies (IOCs). Of the top 20 IOCs, 19 have set methane targets, covering 98% of their production. By contrast, just eight of the top 20 NOCs have set methane targets, covering around a third of production.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData

NOCs lag their publicly traded counterparts in addressing these emissions for many reasons: more limited technical capacity, insulation from investor pressure and civil society, hesitation to disrupt an important source of government income, and constraints on capital due to their frequent role as the government’s “bank account” for a broad range of public needs.

Cost is rarely the main barrier to methane abatement, which is generally affordable or even cost-free. The IEA estimates that just $36bn would suffice to cut most methane emissions from NOCs, with $12bn of that concentrated in low and lower-middle-income countries. This compared with nearly $300bn of free cash flow generated by the top 20 NOCs in 2022.

How finance fits in

How is the financial sector involved? The oil and gas business requires finance to access the huge streams of capital needed for its operations. More than 20 NOCs have listed shares, and many more borrow regularly on debt markets. All of them borrow from banks, often international banks that have committed to reducing the GHG intensity of their lending. Investors that hold sovereign debt in NOC host countries are exposed to risks associated with NOCs and can use this as a pathway to engage with the government. Other financial services that NOCs may use include access to foreign exchange, commodity hedging and insurance.

When investors, lenders and insurers provide these services, they have exposure to the NOCs’ climate and transition risk profile, and an opportunity to raise the importance of methane pollution abatement.

As financial sector actors engage the NOCs on methane, what should they ask for? There are four key points:

- NOCs should measure methane emissions. Despite the availability of a diverse and increasingly affordable portfolio of measurement solutions, too many companies rely on desk-based methods to estimate methane emissions. The most credible way to get on this path is to join OGMP 2.0.

- NOCs should set ambitious methane reduction targets. These should be aligned with the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative’s 0.2% methane intensity target, or near-zero by 2030.

- NOCs should operationalise these targets. This means allocating capital and technical resources and aligning management incentives towards meeting methane goals.

- Leading NOCs should encourage their industry peers. Given the range of NOC capacities, large, well-resourced companies with more experience in methane mitigation should assist their less-resourced peers to get on track. IOCs in joint ventures with NOC partners should share financial and technical resources to address this issue.

The financial sector can also help by providing tailored financial instruments for methane abatement. Sustainability linked bonds, transition bonds and blended finance tools currently used for infrastructure or energy efficiency projects could be adapted, as could other more innovative financing mechanisms such as blue bonds. Establishing a methane bond for companies to access mitigation funds is a logical next step.

A crucial moment

For NOCs that are ready to step forward on methane mitigation, there are extensive resources available within the industry and outside of it, and joining OGMP 2.0 can open the door. The coming months will bring the issue into focus as the global community gathers for COP28 in the heart of the oil-rich Middle East, hosted by the CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. The time has come for NOCs and their finance sector stakeholders to raise ambition on climate and the energy transition. There is no time to waste.

About the authors: Andrew Howell is senior director of sustainable finance at EDF, where he is responsible for engaging with the investor community to help accelerate the energy transition. Andrew Baxter is senior director, energy transition at EDF, where he works with a variety of stakeholders within the oil and gas industry, financial sector and academia to drive continuous improvement in methane emission management and disclosure.

Related Company Profiles

Chevron Corp

Gazprom